Winter Pea for Grain Production in North Carolina: Research Summary

go.ncsu.edu/readext?490797

en Español / em Português

El inglés es el idioma de control de esta página. En la medida en que haya algún conflicto entre la traducción al inglés y la traducción, el inglés prevalece.

Al hacer clic en el enlace de traducción se activa un servicio de traducción gratuito para convertir la página al español. Al igual que con cualquier traducción por Internet, la conversión no es sensible al contexto y puede que no traduzca el texto en su significado original. NC State Extension no garantiza la exactitud del texto traducido. Por favor, tenga en cuenta que algunas aplicaciones y/o servicios pueden no funcionar como se espera cuando se traducen.

Português

Inglês é o idioma de controle desta página. Na medida que haja algum conflito entre o texto original em Inglês e a tradução, o Inglês prevalece.

Ao clicar no link de tradução, um serviço gratuito de tradução será ativado para converter a página para o Português. Como em qualquer tradução pela internet, a conversão não é sensivel ao contexto e pode não ocorrer a tradução para o significado orginal. O serviço de Extensão da Carolina do Norte (NC State Extension) não garante a exatidão do texto traduzido. Por favor, observe que algumas funções ou serviços podem não funcionar como esperado após a tradução.

English

English is the controlling language of this page. To the extent there is any conflict between the English text and the translation, English controls.

Clicking on the translation link activates a free translation service to convert the page to Spanish. As with any Internet translation, the conversion is not context-sensitive and may not translate the text to its original meaning. NC State Extension does not guarantee the accuracy of the translated text. Please note that some applications and/or services may not function as expected when translated.

Collapse ▲Introduction

North Carolina ranks number two in U.S. poultry, egg, turkey, and hog production; but ranks eighteenth in U.S. grain production (USDA, 2016). This results in, on average, a 200-million-bushel-per-year feed grain deficit (Shore, 2015), and necessitates many livestock feed imports. Soybean is imported in large quantities for use as a protein source in livestock feed rations; this is a significant cost for livestock producers in the state.

Winter pea grain could be used to supplement soybean in total mixed rations fed to livestock because of its high protein concentration levels. Concentrations of protein and starch in pea grain range from 15 to 35% and 35 to 50%, respectively. Peas can be fed directly to livestock, unlike soybeans which require heat processing prior to animal consumption (Miller et al., 2005). Additionally peas have low allergenicity and contain some amino acids that are deficient in small grains. Pea can be grown over the winter in North Carolina, and therefore would not be competing with soybean acreage during the summer.

Winter pea can be grown in mixture with wheat and the two species can be harvested simultaneously for grain. Growth in mixture with small grains can help reduce pea disease incidence, reduce lodging, and can increase total grain yields.

Minimal effort has been devoted to investigating the grain potential of winter pea in North Carolina and a regional screen of available winter pea cultivars for grain production in North Carolina has not occurred.

Objective

The objective of this experiment was to identify winter pea cultivars that can be grown in monoculture and in mixture with wheat for grain production in North Carolina.

Methods

Experimental sites: Studies were conducted from 2014 to 2016 at the Central Crops Research Station in Clayton, NC, the Caswell Research Farm in Kinston, NC, and the Piedmont Research Station in Salisbury, NC. The Clayton sites were a loamy sand, the Kinston sites were a sandy loam, and the Salisbury sites were a clay loam. Phosphorous and potassium were applied as necessary based on NDCA recommendations. Nitrogen fertility was not applied at any sites. Preemergence herbicides were used for weed control at several study sites; no postemergence herbicides were used and the mixture was relatively competitive with weeds in the spring.

Winter pea cultivars and genotypes: Nineteen winter pea genotypes were screened for grain potential. This included twelve released cultivars: CAH-11, Chelan, Common, Fenn, Glacier, Granger, Lynx, Melrose, Racer, Romack, Specter, and Windham, and six advanced USDA-ARS breeding lines: PS07300136W, PS09300095W, PS10300120W, PS10300121W, PS06300028W, and PS0017018W. We also screened the current winter pea cultivar readily available in North Carolina (Nature’s Choice (NC)). Winter pea seed size varies widely by cultivar, therefore we seeded the winter peas using a plant population of 180,000 seeds/acre in monoculture (approximately 90 lbs/acre).

Pea emergence at the Piedmont Research Station in Salisbury, NC.

Variation among pea genotypes.

Winter pea and wheat mixture: Each winter pea genotype was tested not only in monoculture but also in mixture with three winter wheat cultivars of differing maturities. These included USG 3120 (early maturing), FeatherStone VA 258 (medium maturing), and NC Yadkin (late maturing). Winter pea was seeded in mixture at 120,000 seeds/acre (approximately 60 lbs/acre) and the wheat was seeded at 375,000 seeds/acre (approximately 30 lbs/acre).

Pea and wheat grown in mixture.

Planting and harvesting: The research plots were planted from late September through mid-October using a small-plot grain drill. The plots were harvested in June using a small-plot combine. Both the monoculture pea plots and the mixture plots were harvested with the soybean bottom sieve in the combine. Generally, the wheat cultivars were mature prior to most pea genotypes. This allowed for a simultaneous grain harvest as soon as the peas reached physiological maturity. Some of these pea genotypes are indeterminate (the pods will not all mature at the same time); identifying the correct time to harvest was the most challenging part of harvesting the peas. Pea lodging following late spring storm events also slowed down harvest, however it was possible to pick the lodged peas up off the ground with the combine for grain harvest. At one site, we did see reduced pea lodging when the pea was planted in mixture with wheat compared to growth in monoculture.

Harvesting winter pea and wheat simultaneously using the soybean sieve in our combine.

Pea lodging following a spring storm.

Collected data: Pea cold tolerance, pea disease incidence, pea maturity, and pea and wheat grain yield.

Results

Pea cold injury: Most pea genotypes survived the North Carolina winter with minimal cold injury. The cultivar Racer was the earliest flowering pea genotype and experienced the greatest cold injury across sites; we would not expect this cultivar to consistently survive the North Carolina winter. There was also minor cold injury observed occasionally with the cultivar Romack, but the plants were able to outgrow this injury and grain yield was not affected. Growth in mixture with wheat did not prevent Racer or Romack from experiencing cold injury.

Cold injury varies between pea genotypes at the Caswell Research Farm in Kinston, NC in February 2015.

Early spring cold damage in one pea genotype at the Piedmont Research Station in Salisbury, NC.

The purpling on this winter pea genotype may be symptomatic of cold stress, however the genetics in some pea genotypes express purpling all season independent of environmental stresses.

Pea disease: Disease pressure was variable across our sites. Pea growth in mixture with wheat did not reduce disease incidence compared to pea growth in monoculture. We did not make any fungicide applications to control diseases. We had severe powdery mildew infestations across several sites in late spring. When powdery mildew appeared, it affected all pea genotypes screened. We also had Ascochyta leaf blight at several sites. The most severe disease complex affecting winter pea in North Carolina is the Sclerotinia complex. We had severe late-season Sclerotinia pressure at our Kinston sites in both years, and this prevented grain harvest across all winter pea genotypes at this site. We also had severe late season disease pressure in several pea genotypes at the Salisbury sites. Breeding peas that have Sclerotinia resistance is a long-term goal in our research program as pea growth is severely restricted in the presence of Sclerotinia pressure. Future research is merited on controlling diseases in pea in the Southeast and the affect that pea diseases may have on other crops in the rotation. We also saw a lot of aphids in our winter peas in late spring; aphids are vectors of several viruses that infect peas. We did not control insects in our trials; aphid control might be an important consideration for pea production in the region.

Powdery mildew presence.

Pea chlorosis caused by various pea diseases.

Sclerotinia pressure at the Kinston sites.

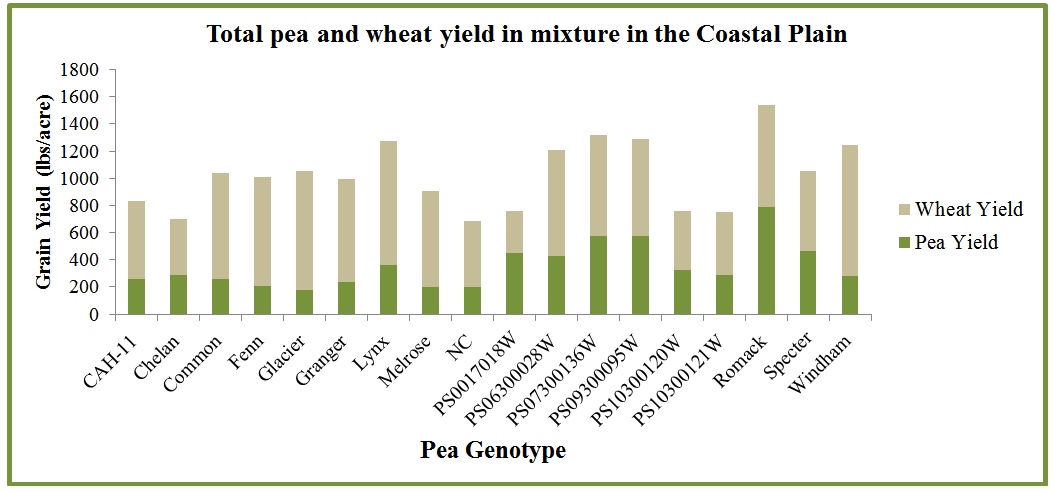

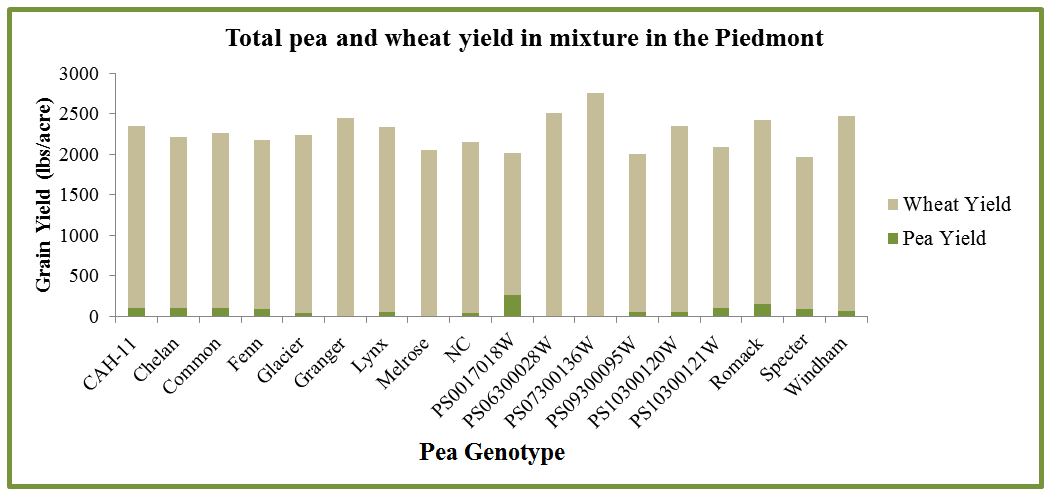

Grain yield: Pea yields were similar whether pea was produced in monoculture (seeded at ~90 lbs/acre) or in mixture with wheat (seeded at ~60 lbs/acre). The small grain may have helped pea growth by allowing the pea to climb off the ground and achieving more access to sunlight leading to higher rates of photosynthesis. Both in the Coastal Plain and in the Piedmont, pea yields were lower than typically achieved in the Pacific Northwest US where winter peas are more commonly produced for grain; it is important to remember that we did not control for weeds, insects, or diseases at the sites in North Carolina. Pea grain yield can be severely restricted by excessive heat during flowering. When these peas started flowering (mid to late April), it was likely too hot already in North Carolina for good grain fill. If we could access winter pea germplasm that flowered earlier (March) but also had the cold tolerance necessary to survive the North Carolina winter, we might be able to enhance pea grain yield in this region. Pea yield in mixture with wheat was higher in the Coastal Plain; combined grain yield for several pea genotypes exceeded 1,200 lbs/acre with the pea and wheat contributing similar proportions of overall grain yield (Figure 1). Pea yields in mixture with wheat were very low in the Piedmont (Figure 2). Wheat yields in the Piedmont were surprising (35-40 bu/acre), considering wheat was planted at ~30 lbs/acre (Figure 2). In both the Coastal Plain and the Piedmont, wheat was planted at ~30 lbs/acre and no N fertilizer was provided to the mixture. In the Coastal Plain, wheat growth was restricted by the lack of N, but this allowed the legume a chance to compete in the mixture. In the Piedmont wheat was very competitive with pea, and dramatically reduced pea yield in all pea genotypes even though wheat was planted at a low seeding rate (Figure 2). There was higher residual N at our sites in the Piedmont compared to the Coastal Plain; seeding wheat at 30 lbs/acre in mixture may be too high in sites with high residual N.

Figure 1. Total pea and wheat grain yield in mixture as affected by pea genotype averaged over wheat cultivar in the Coastal Plain (Clayton 2014/2015 and Clayton 2015/2016).

Figure 2. Total pea and wheat grain yield in mixture as affected by pea genotype averaged over wheat cultivar in the Piedmont (Salisbury 2014/2015 and Salisbury 2015/2016).

Conclusions

Winter pea genotypes have not been screened for grain production previously in North Carolina. Our results identified some winter pea genotypes that are superior for grain production in our region, however, pea yields were still low compared to other US regions. Limited research has been conducted on the agronomics of winter pea production in this region. Our results do show that winter pea and wheat can be grown in mixture and harvested simultaneously with minimal harvest losses. Weeds, diseases and insects were not controlled in this experiment; future research will focus on investigating agronomic practices that can increase grain yield (i.e., appropriate seeding rates, planting dates, herbicides, insecticides, fungicides). We will continue to work with the USDA-ARS winter pea breeder to obtain earlier flowering pea genotypes that may be less susceptible to heat injury during flowing and have enhanced disease resistance.

We are aware that some growers are producing yellow peas (planted in December/January and harvested in April/May) in Southern portions of North Carolina and in South Carolina. These yellow peas are considered a spring pea. We have not investigated these yellow pea cultivars or the agronomic production practices associated with them at NC State yet, but we intend to start research trials on spring yellow pea production in North Carolina this fall.

Growers visit the pea and wheat mixture plots at the Piedmont Research Station.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the North Carolina Dairy Foundation and Southern SARE for supporting this research. We are excited about the future of pea in North Carolina as an alternative protein source in livestock feed rations!

References

Miller, P., K. McKay, C. Jones, S. Blodgett, F. Menalled, J. Riesselman, C. Chen, and D.

Wichman. 2005. Growing dry pea in Montana. Montana State University Extension Service. Available at: www.msuextension.org/pspp/documents/GrowingDryPea.pdf

Shore, D. February 5, 2015. Growing the Grain Industry: Solutions to benefit both crop and animal producers. North Carolina State University, College of Agriculture and Life Sciences News. Available at: https://cals.ncsu.edu/news/growing-the-grain-industry/

USDA/NASS. 2016. 2016 Agricultural Statistics, North Carolina. Available at: https://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/North_Carolina/Publications/Annual_Statistical_Bulletin/index.php

This publication was prepared by Rachel Atwell Vann, Chris Reberg-Horton, Miguel Castillo, Rebecca McGee, and Steven Mirsky